UNCW and Duke researchers uncover surprising limitations in whale eyesight, reshaping understanding of marine mammal perception.

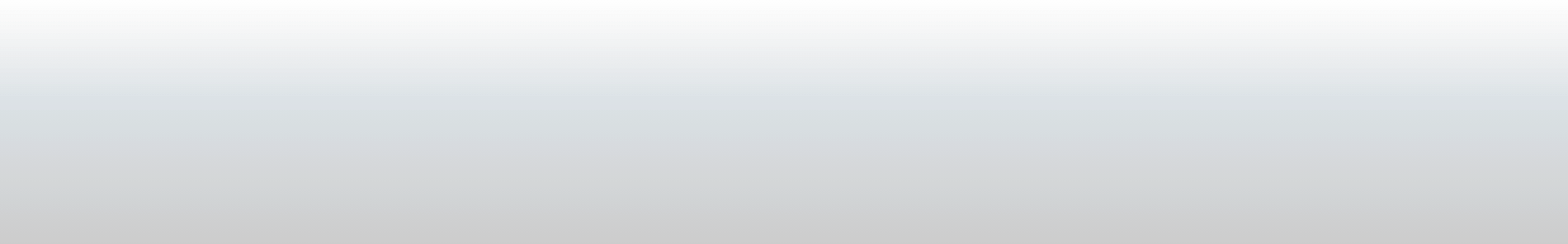

Photo: Michael Spencer/UNCW

A new study by researchers at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and Duke University finds new knowledge of the humpback whale eye, revealing that these iconic marine giants possess surprisingly limited visual acuity—raising important questions about how they see their open ocean environment and how human activity may affect them.

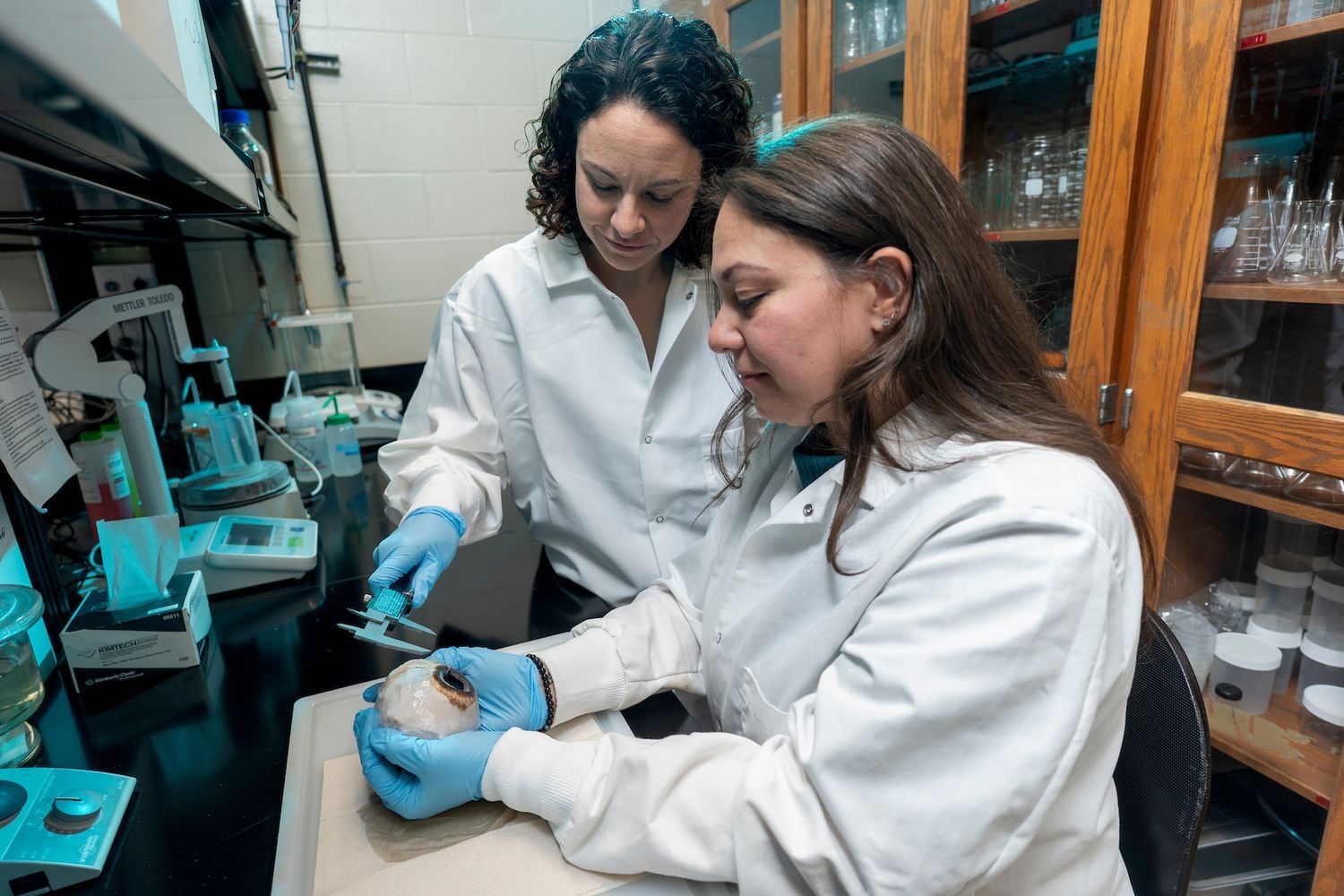

Despite their large eye size, humpback whales’ vision was measured at just 3.95 cycles per degree (CPD)—lower than predicted—meaning they can detect large, simple shapes from a distance, but need to be very close (within 3–4 body lengths) to see fine details.

Using anatomical and perceptual models, the researchers simulated how humpbacks perceive their surroundings, including potential threats like fishing gear. The models suggest that while whales can see large objects from afar, detailed features are likely only visible at close range.

“This work helps fill a major gap in our understanding of the sensory ecology of large whales, how humpbacks experience their world,” said Lori Schweikert, assistant professor of biology and marine biology.

The research, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, began as an undergraduate Honors thesis by UNCW alum Jacob Bolin ’23, lead author on the paper. Vanessa Moreno, a graduate student who helped mentor Bolin in Schweikert’s lab, is a co-author. The UNCW Marine Mammal Stranding program provided the whale eye specimen that was collected by William McLellan from an animal that stranded in Thorofare Bay, North Carolina, and was archived for over a decade prior to the study. UNCW’s Richard M. Dillaman Bioimaging Facility facilitated the data collection and imaging for the study.

While visual perception is a part of a whale's sensory toolkit, understanding it is essential—particularly for mitigating human-induced threats like entanglement. This understanding could lead to designing fishing gear to reduce entanglement based on whale visual capabilities.

The study encourages future research that links physiological vision data with field reports from real-world interactions and advances understanding of cetacean sensory biology. The findings raise new questions about how whale vision evolved and how these animals adapt to an ever-changing human-influenced ocean.

This article has the following tags: CSE - College of Science & Engineering Academics myUNCW - Students myUNCW - Faculty & Staff CSE Research & Innovation Biology & Marine Biology CSE Students & Alumni Research & Innovation